- Praful Shah

Aged 2 years old, I came to England in 1958. I had experienced very little prejudice or racism throughout my early life. But that changed in the mid 1980s when I discovered racism rearing its ugly head in the form of fervent opposition to Hindus worshipping at Bhaktivendanta Manor. ‘No Browns in my back yard’ was a stance taken by some active characters in Letchmore Heath and Hertsmere Borough Council (HBC) members, cleverly disguised as a planning permission matter.

“If you stand for nothing, you’ll fall for everything.”

When I engaged in the fight to save Bhaktivendata manor, I remember thinking it was not about the planning permission or the semantics, but about freedom of worship.

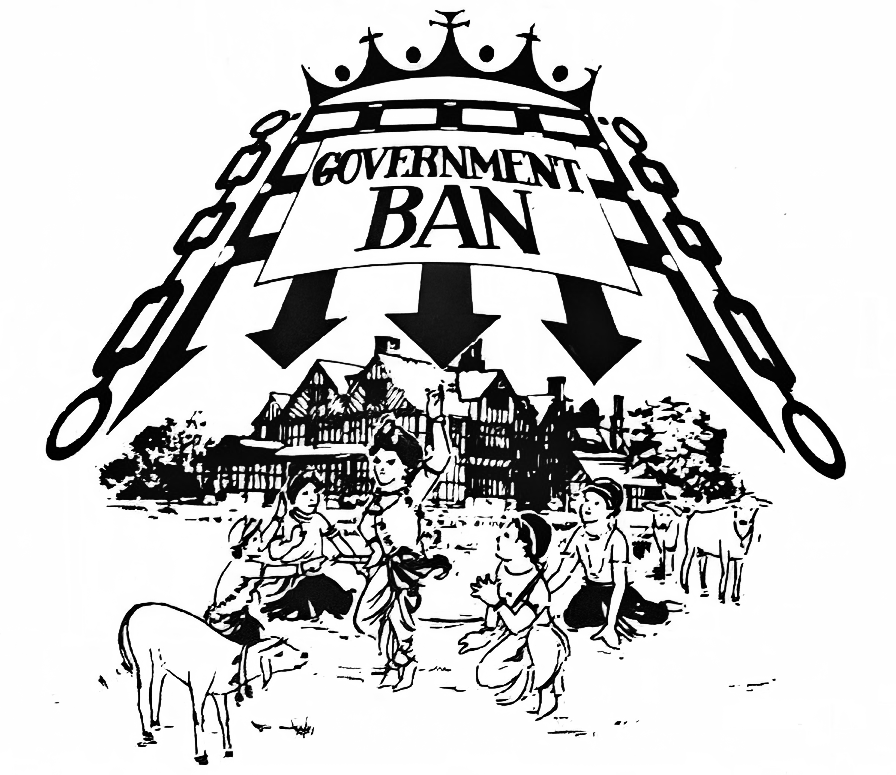

Throughout the majority of the ten year battle (1986 – 1996), the HBC based its case of closing the Manor on a clause that only allowed it to be used as a place of theological studies and not a place of worship. They had previously permitted six days of religious festivals per year. However, over many years, the number of Hindu devotees attending the mandir increased exponentially. This worried a few villagers who complained to the HBC. The legal challenges began.

Initially, they took ISKCON to court over noise complaints. They lost the case. They then took us to court over the number of cars creating traffic on the road. They lost the case again. They had to pay the Temple the legal costs for both actions. Still, they persevered. Eventually, they came to rely on the ‘theological studies’ clause. Many hearings and public enquiries took place over the decade.

Until 1990, our message was simple: ‘Save the temple’. A public enquiry that refused our appeal to keep the temple open for worship gave two years for the HBC and the Manor to find a mutually acceptable solution. If no solution were found, we would be served with an Eviction notice. The HBC were never intending to play ball and, instead, pretended to help us to find another site to relocate. In reality, they began a campaign of show and propaganda to win the hearts and minds of people to their cause whilst wasting away the two years.

Staunch supporters of the temple, especially Councillor Frank Ward, decided to form a defence movement. We were called the Hare Krishna Defence Movement (HKDM). It was chaired by Narish Chadha, in whom I saw traits of Yudhistir, the eldest of the Pandava brothers. He was honest, straight talking, reliable and developed plenty of fantastic strategies we relied on in the coming years. We nicknamed Frank Ward ‘Arjun’ as he seemed capable of battling on all fronts and inspiring crowds to take up the cause. CB Patel, the proprietor of the Gujarat Samachar, was a hidden affiliate. His newspaper followed the developments closely throughout the ten year battle and helped unite our community throughout the country. There were about ten other members, including myself. I was also a Patron council member. Approximately twenty of us were in charge of raising funds and mobilising supporters to attend events.

The first big fundraiser was to cover the legal costs of the upcoming 1990 Public Enquiry. We organised a sponsored walk from Wembley to the temple to raise £100,000. Help, support and publicity to make this event a success came from the famous actor Rishi Kapoor and star cricketer Sunil Gavaskar, who both joined the walk.

As the March 1992 two year deadline approached, we hosted a mass demonstration. Coaches of people from all over the country and a whole host of backgrounds and religions showed up to march in solidarity with us and ‘Freedom of Worship’. We congregated at Lincoln’s Inn Fields in Holborn at 12pm and walked to the park behind the Imperial War Museum. It was beautiful to see every generation walking side by side. My 5 and 8-year-old children, wife and parents all marched together. Astonishingly, 35,000 people attended. Bizarrely, but perhaps unsurprisingly, the British newspapers reported the following day that only 5000 marchers were present.

The HKDM decided that the only course of action left for us to delay an Eviction notice was to go to the European Court of Human Rights. Unfortunately, the ECHR ruled in April 1994 that ISKCON’s appeal was inadmissible. This was gut wrenching to hear and we were at our lowest ebb. We had to do something radical and not just the usual marches and demonstrations.

One of my most unforgettable moments in this journey with the HKDT, was the peaceful mass demonstration we held outside the Houses of Parliament in May 1994 to lobby MPs directly with our concerns. Prime Minister’s Question Time was Thursdays from 3.15pm so many MPs were present. At 3pm, when Big Ben struck, fellow HKDM members and I led the crowd to the middle of the road bellowing out a cry of ‘Besejawo, Besejawo’ (Sit down, sit down). London traffic ground to a halt for an hour. I was sitting on the road with some Masi’s when a police officer bent over and whispered in my ear ‘You’re a real agitator’ and grabbed my arm pulling me to my feet and dragged me off. He added, ‘I wouldn’t come back.’ I’d never felt prouder or had more strength in my conviction. Many were arrested that day and my thoughts were how heroic they all were.

A few weeks passed and Shrutidas presented me with a photo of myself being dragged off the street by a police officer. He told me that a devotee recognised me in the photo and wanted me to have it. I wish Shruti has told me the person’s name to thank them as the event was a cherished lifetime memory for me.

In July 1993, we organised chanting in the village. I set up two tables at the front gates with Japa beads available for followers to pick up and do rounds. Hundreds of young devotees attended. A car sped past with a person shouting ‘Get out, Muslims!’ It struck me just how much blind ignorance and inherent prejudice there was from the local villagers towards us.

During a large gathering outside the Civic Centre, Mr P Marsh complained that his car tyres had been slashed with a knife. The bill was for £400 and Akandidas decided that the temple would pay the cost to him. We truly believed it was not an act committed by a Hindu radical but an imitator who wished to agitate and incite Mr Marsh further in his actions against us.

By 1996, we were elated when the Labour Party took control of the HBC as we felt that would stack the building of an access road to the temple and ability to legally worship at the mandir more in our favour. And so it did.

‘We’ve won. The government have granted us the permission. The temple is saved!’ – Naresh Chadha rang me in 1996. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. My wife and I were ecstatic and started calling our friends with the good news. The fight had paid off.

I often reflect about members of the HDKM and Patron’s Council achievement. Many of us were young parents who had just started our businesses and families. As first generation immigrants, most of us had little to no financial support and were facing the challenges and pressures of having young families. But we sacrificed and spent many evenings and weekends channelling our energy towards something more important. We were just ordinary people – accountant, electronics specialist, optician, printer and many more. It just shows what ordinary people can achieve when we put our minds to it.

Had the fight never taken place, Bhaktivedanta Manor would never have been able to cope with the ever increasing worshippers attending over the last 25 years, especially during Janmashtami.

We were united in fighting for something we valued for our future generations. We hope they carry forward this responsibility in our absence.